Minnesota Politics, Immigration, and Family History

Family history is a way to encounter interesting stories, difficult truths, and to expand the understanding of how your family's story intersected with larger forces and events. Throughout this section of the blog, I will turn that family history lens onto Minnesota’s politicians and use it as a way to examine Minnesota's history, and to teach people how to use the many available records for their own family history research. I will eventually cover many people, but anyone observing Minnesota in January 2026 will understand why I would start with immigrants and their children and grandchildren. We are ongoing shapers of Minnesota history because we are inextricable from Minnesota.[1]

Our state has historically been home to large numbers of immigrants relative to our population. From the state’s formation in 1858 through the end of the 1800s, Minnesota’s foreign born population[2] made up about 33% of the state’s population. Between 1900 and 1920, it was over 25% of the state’s population. In fact, there were more foreign born residents counted in the 1900 (28.9% of the state; 505,318 people) and 1910 (26.2% of the population; 543,595 people) federal censuses than in the 2023 ACS (8.6%; 495,352 people). Minnesota was among the ten states with the highest percentages of foreign born residents in every census year from 1860-1920. Minnesota—from its inception as a state—has had immigrants and their descendants shaping our culture and politics.

Table: Minnesota’s foreign born population enumerated in the U.S. Census, 1860-2000[3]

| Census Year | Percent Foreign Born | Total |

|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 34.1% | 58,728 |

| 1870 | 36.5% | 160,697 |

| 1880 | 34.3% | 267,676 |

| 1890 | 35.9% | 467,356 |

| 1900 | 28.9% | 505,318 |

| 1910 | 26.2% | 543,595 |

| 1920 | 20.4% | 486,795 |

| 1930 | 15.2% | 390,790 |

| 1940 | 10.6% | 295,373 |

| 1950 | 7.1% | 210,570 |

| 1960 | 4.2% | 143,878 |

| 1970 | 2.6% | 98,056 |

| 1980 | 2.6% | 107,474 |

| 1990 | 2.6% | 113,039 |

| 2000 | 5.3% | 260,463 |

Minnesota: January 2026

Over the course of December 2025-January 2026, the state of Minnesota has seen tremendous and increasing federally-sanctioned violence against anyone with an accent or skin color that isn’t like mine and is a place (as I write this) where anyone who steps outside their house to blow a whistle or yell or observe or film risks violence—even death. That is the context the people I know and care about live in right now. The federal government uses violence and shackles because it creates an illusion that Americans can choose to believe: these are the worst of the worst. It is theater, but the harm is real.

These times are dangerous and the language is manipulative. “Illegal immigrant” conjures a picture for some of an inherent criminality and, accompanied by those images of shackled and terrified people and the fact that some were attending court confirms a story that a surprising number of Americans seem to want to believe is real. But the presence of a person born elsewhere in America is not evidence of lack of authorization to be here, nor is a perfunctory immigration court check-in. A person could be on a visa, allowing them to stay for a certain length of time for school or work or many other reasons—it is so complex that the U.S. Department of State has a “visa wizard” to help people identify what sort of visa they should apply for. On top of visas, there are humanitarian processes[4] for refugees, people seeking to relocate to the U.S. due to persecution or torture in their home country (also known as asylum[5]), temporary protected status, and others. Green cards offer permanent residency and the ability to live and work in the U.S. And, finally, there is citizenship.

On the streets of Minneapolis and St. Paul and across the state, it is clear that the current stance of the federal government is that everyone is “illegal” until and unless they’re able to prove otherwise, and American citizens must endure any violence the agents of the federal government desire—including hours, days, or even weeks of detention. Residents, no matter their authorization or lack thereof to be here, must endure worse. It is inhumane, chaotic, and horrifying.

The Quota System: Which Immigrants are Desirable?

Many pieces of legislation about who is and is not allowed to come to the U.S. and become a citizen have been written going back to 1790. The significant drop in the population of foreign-born Minnesotans during the 1960s-1990s was tied to the stringent quota systems passed through legislation in 1917 and 1924 that affected the entire United States with a goal of sharply reducing immigration from areas outside of Northwest Europe, with 1924's quotas basing the percentage of allowable immigrants from a given country on the percentage that country was represented compared to the total U.S. population in the 1890 census (and fully excluded immigration from Asian countries)—this dramatically lowered the number of immigrants allowed from countries in Eastern and Southern Europe like Poland and Italy, which was the intent. As the future President Woodrow Wilson wrote in 1902 of the wave of European immigrants coming after 1890:

“Immigrants poured steadily in as before, but with an alteration of stock which students of affairs marked with uneasiness. Throughout the century men of the sturdy stocks of the north of Europe had made up the main strain of foreign blood which was every year added to the vital working force of the country, or else men of the Latin-Gallic stocks of France and northern Italy; but now there came multitudes of men of the lowest class from the south of Italy and men of the meaner sort out of Hungary and Poland, men out of the ranks where there was neither skill nor energy nor any initiative of quick intelligence; and they came in numbers which increased from year to year, as if the countries of the south of Europe were disburdening themselves of the more sordid and hapless elements of their population, the men whose standards of life and of work were such as American workman had never dreamed of hitherto.”[6]

As a descendent of some of these meaner, hapless, sordid people myself, it surprises me how short our memories are about who is included vs. excluded as being American enough (or acceptable enough to become American).

When I was in my early 20s and living away from Minnesota, it became very hard to visit both the Twin Cities and the Iron Range. During one of my belated visits, my grandmother met me at the door of her small Chisholm house and asked me if I "needed a tour," and if I was "ashamed of your old Bohunk grandma." My response to her was "no." To my friends it was "no one knows what a Bohunk[7] is anymore."

It was true that kids I grew up with didn't know the derogatory terms that got thrown at people like my grandparents, but that wasn't really the point. It simply didn't matter if they did. I didn't have words for the ongoing American negotiation and renegotiation of ethnicity and race, but it was right there in that exchange.[8] Another way you can watch its evolution is how identity is argued and evolves via what is written in newspapers.

Hyphen-Americans

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, you could find many articles discussing "hyphen-Americans"—whether it was good or bad...or traitorous. In a speech titled “Americanism,” former President Theodore Roosevelt devoted an entire section to this term, concluding it with:

“For an American citizen to vote as a German-American, an Irish-American or an English-American is to be a traitor to American institutions; and those hyphenated Americans who terrorize American politicians by threats of the foreign vote are engaged in treason to the American Republic.”

The debate over who is or is not American is as old as the country. It's one thing I find so interesting in family histories—how race, ethnicity, religion, and other identities affect the boundaries of a person's life depending on when they lived.

In terms of debates about "hyphen-Americans," there are many articles and letters to the editor to choose from in just the Minnesota papers from the turn of the 20th century. It is important not to read these papers as objective—they were partisan and had their own goals.[9]

The Irish Standard's brief news item gets to what is underneath these battles for the European immigrants without British ancestry and multigenerational American roots—who gets to control identity and why do they think it's theirs to control?

Regardless of whether an Irish-American or German-American agreed with or disagreed with the use of the hyphen, what they saw in the speeches against immigrant communities was hypocrisy. The same people who created the environment in which immigrant communities lived—who at times excluded them over their accents or were suspicious of them due to their religion—were angry at the immigrant communities for their identity.

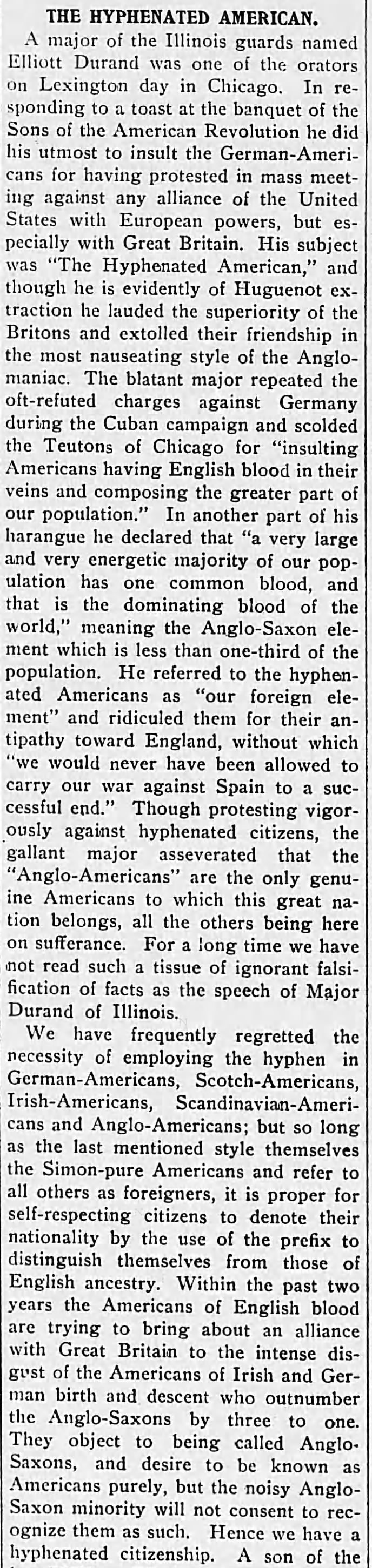

The following article ultimately laments the need to use hyphens, but quotes from a speech given at a Sons of the American Revolution banquet that demonstrates why the writer still perceived them to be necessary. The speaker “scolded the Teutons[10] of Chicago for ‘insulting Americans having English blood in their veins and composing the greater part of our population.'” When the current vice president says: “you don’t have to apologize for being white anymore," his words are racist, but they also map well onto the haughty xenophobia of the Sons of the American Revolution speaker.

Violent Immigrants

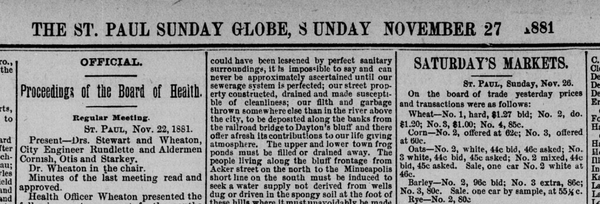

The Minnesotian never stopped fretting about the Irish and had countless articles over the years alleging voter fraud, intimidation, and election interference by the Irish immigrants. It is best to understand the paper as hyperbolic, passionate, and infused with fairly substantial anti-Irish sentiment; not as objective.

I include these two stories (from the same column of the same page of that issue of the Minnesotian) because it is so reminiscent of how overwrought and melodramatic the anti-immigrant language is today, though now we have the added layer of racism.

The Irish (and their children and grandchildren) became very politically powerful in St. Paul, but they were also politically organized from the start and running slates of Irish candidates in elections. The Minnesotian teemed with prejudice that can't be explained only through political differences—they published fake letters to the paper written in a mimicry of Irish accents and speech and accused the Irish of violence in multiple elections. They also insinuated in the second article that the Irish retained jobs instead of Americans—"What are we coming to?"

As they say, history doesn't repeat itself—but it does rhyme.

Be safe, Minnesota. Be good neighbors. Stand with us.

The first politician covered in this will be Governor Rudy Perpich, a child and grandchild of Croatian immigrants to the Iron Range.

Minnesota is as complicated as everywhere else in America, and immigration stories can focus too much on thriving despite significant struggle and not the broader power dynamics and environment into which these immigrants came. For example, Irish and German immigrants who arrived in Minnesota prior to and in the early years of statehood benefitted from governmental policies that provided them easy access to land, which made these early Minnesotans active participants in and beneficiaries of the colonization and settlement of the state to the detriment of Dakota and Ojibwe people here. You could flee starvation and oppression in Ireland during the Great Famine and find yourself participating in an entirely different system of oppression in this country. For a greater understanding of the land and treaties, see the website Treaties Matter, which goes into much more detail. ↩︎

Not all people residing in the U.S. who were born in another country intend to become citizens, so foreign born is used as it is in the census. ↩︎

Gibson, Campbell and Kay Jung, "Historical Census Statistics on the Foreign-Born Population of the United States: 1850 to 2000," p. 60-69.

Data from "Table 14. Nativity of the Population, for Regions, Divisions, and States: 1850 to 2000." ↩︎These links go to the Wayback Machine because the current information on the website is not useful for understanding what processes look like during normal times. ↩︎

The president has insisted on conflating people fleeing persecution (asylum seekers) with "mental asylums." This is on purpose, and writing it off as ignorance is unwise. ↩︎

Wilson, Woodrow. "A History of the American People." Vol. 5. Harper & Brothers: New York and London. 1901. https://archive.org/details/historyofamerica0005wood_p4m8/page/218/mode/2up ↩︎

Do you know what a bohunk is? It was basically a slur used against people from east and southeastern Europe in the early 1900s, who typically worked as laborers. ↩︎

I encourage anyone descended from the roughly post-1850 waves of immigrants to read books that explore immigrant race and identity like Whiteness of a Different Color: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race. ↩︎

The Irish Standard was a Democratic newspaper, and note that the MNHS description of it discusses the stance toward Irish-Americans. The Minnesotian was a Whig newspaper which became a Republican newspaper once the former party had met its fate. ↩︎

German-Americans. ↩︎