Cholera Infantum: Poverty, Food Safety, and Preventable Deaths

In July of 1881, fifty infants and toddlers in St. Paul died by the same cause: “cholera infantum.” This is not “cholera,” the illness caused by the Vibrio cholerae bacteria, but rather a general term for any number of illnesses that presented with similarly severe gastrointestinal symptoms that occurred more frequently in the summer months. In the St. Paul Death Register Project, I think a lot about the ways government can act as a positive force—making people safer and less vulnerable—and what it means when the people in charge make choices that make us less safe and more vulnerable. Interventions put in place to reduce infant mortality—specifically through developing nutritious infant formula, educating people about the benefits of breastfeeding, and providing access to pasteurized, unadulterated milk (along with food safety monitoring and our ability to test for specific bacteria when a child does get sick) has rendered this vague cause of death obsolete.

Poverty and Access to Safe, Nutritious Food

With the United States federal government shut down, the current administration has decided to play political chicken with the lives of children. If nothing changes in the next day, the funding for WIC (the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children) and SNAP (the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) will be cut off on November 1, 2025. The callous disregard for the health of children led me to write specifically about cholera infantum as an example of what life was like many decades before legislators like Minnesota senator Hubert H. Humphrey[1] passed laws supporting children’s nutrition (he sponsored the legislation establishing WIC as a 2 year pilot).

Life before a social safety net, food regulations, and nationwide disease prevention was harder than most Americans living today can conceive of. As a parent without access to food for your child, you could watch your child starve—succumbing to what was called “inanition” or “marasmus” in the death registers (both meaning severe malnutrition and starvation). Five children died of inanition in St. Paul in July 1881; one of marasmus.

Poverty intensifies every risk, and maternal mortality or the serious illness of a mother affected whether a child could be fed breastmilk. The 1880s were a time before infant formula, so no good options for food existed if breast milk was not available—anything else was risky in terms of both nutrition and infectious disease.

Cholera Infantum

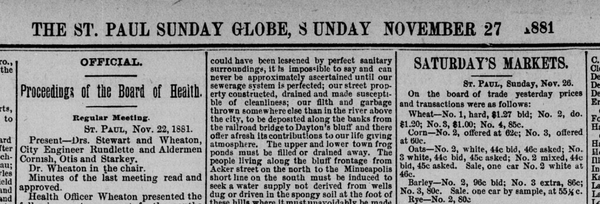

The deaths during that summer in St. Paul were not unusual; they happened every year in warmer months—cholera infantum was sometimes called “summer complaint,” a strangely innocuous-sounding illness when contrasted with its consequences.

So what is cholera infantum? It is an “illness [that] consisted of 8-12 days of diarrhea followed by vomiting, thirst, dehydration, and emaciation. Sick infants would be unable to retain any nourishment and would continue having vomiting and diarrhea until they fell into a coma and eventually died.”[2] Whether the cholera infantum a child in 1881 died of was E. coli, Salmonella, or Shigella wasn’t something medical professionals could document at the time, and researchers are cautious about making definitive statements about the causes of these gastrointestinal infections.[3]

Even in the 1800s, the food people substituted for breastmilk was seen as a likely culprit—though even if they tried to find ways to provide safe food to their children, it was difficult.

“The demand for clean milk was especially high in the homes of the poor, where it was a necessity for the mother to work, or the mother was too ill to breastfeed the child. In some cases, mothers took matters into their own hands and fed their infant proprietary foods, such as Mellin’s milk modifier or Borden’s sweetened condensed milk, which were advertised directly to mothers through magazines and at grocery stores.”[4]

These diets led to malnutrition, including scurvy and rickets in infants.[5] Pasteurized milk was not yet available in stores, and you could contract diseases like typhoid, scarlet fever, diphtheria, and tuberculosis from unpasteurized milk.[6]

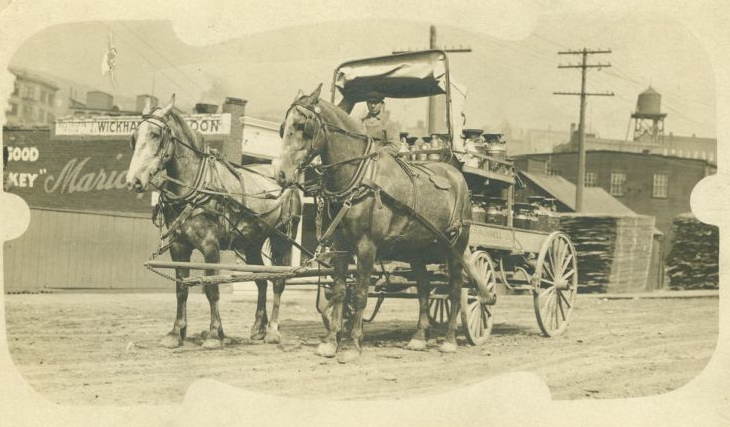

On top of this, milk was sometimes transported without refrigeration in uncovered containers. It was "grey colored and tasted bad. To the spoiled milk, middleman buyers added chalk, bicarbonate of soda, molasses, and sugar to improve the color and hide the spoiled milk taste. In addition, middleman buyers would often skim the cream off the milk and added water without buyer's knowledge."[7]

L. Emmett Holt’s 1897 medical text, The Diseases of Infancy and Childhood, further described issues with contaminated milk:

“The view almost universally held at the present time regarding summer diarrhea is that it is of infectious origin. The grounds for this opinion are briefly as follows: A certain temperature is required, which is the same as that at which the growth of bacteria begins to be very active. This disease prevails to the extent to which other food than breast-milk is given to infants. Thus it affects infants after weaning, and those younger who are partly or entirely fed upon cow’s milk, or at least who are not nursed. Cow’s milk, as ordinarily handled, contains in summer an enormous number of bacteria (p. 144), which increase directly with the age of the milk and the height of the temperature at which it is kept. It has been shown by Vaughan and others that certain substances may be produced in milk which are capable of exciting in animals all the symptoms of severe cases of cholera infantum. In the milk which children had been taking when such symptoms developed, the same toxic substances were found. The two diseases to which summer diarrhea has the closest analogy—typhoid fever and cholera—are both due to a specific infection.”[8]:

In his section on prevention, he wrote that:

“Maternal nursing should be encouraged by every possible means. No weaning should be done, if it can be avoided, during summer. Nothing is better established than the close relation existing between artificial feeding and diarrheal diseases…The general rules laid down elsewhere on the subject of artificial feeding must be carried out, as to the quantity of food, frequency of feeding, modification of cow’s milk, and all matters related to the care, transportation, and sterilization of milk…No greater work of philanthropy can be done among the poor in summer, than to provide means whereby pure, clean milk for young children can be supplied at the price now paid for an inferior article.”[9]

A hygienic milk supply was a feature of infant welfare campaigns throughout the early 1900s, and was noted as one of four “essential features” of those campaigns[10] by Grace L. Meigs, the first director of the Child Hygiene Division of the Children’s Bureau of the U.S. Department of Labor.

Cholera infantum was not the topic of her paper; it was a call to action that discussed prevention of gastrointestinal diseases (such as cholera infantum) and respiratory diseases, as well as improving prenatal care and medical care during birth. Milk was not her only focus, but it was a significant focus in many cities as they tried to increase access to unspoiled, unadulterated milk. “Although city health departments set standards and tested the chemical and bacteriologic content of milk, voluntary organizations opened milk stations in poor neighborhoods, where mothers were drawn by cheap or free milk. In some cities, physicians and milk producers cooperated to offer milk that was more expensive but certified pure. A few agencies also provided directories of wet nurses, but they were the exceptions. By 1920, pasteurization of the milk supply replaced these various strategies in most American cities.”[11]

In Memory of the St. Paul Children

I typically map out a single family, looking at the different ways the family members are affected by disease or lack of treatment or prevention options and telling their stories. This is difficult with infant deaths, most significantly because there is almost no information in the death register beyond the name, age, date, and cause of death. There often isn’t enough evidence to link a child with their family if other possible records exist, and misspellings of names are frequent (as many of these likely are). Brick walls abound.

In place of that storytelling work, I wanted to honor these St. Paul children who died in July of 1881 by the names listed in the death register.[12] The decisions our government makes are not abstract—we are a wealthy country and every child who cannot access safe and nutritious food due to poverty is suffering from a choice made by legislators and a president who do not have to worry about whether their own children are fed. The children below would not have died of this illness if their parents had access to safe and nutritious food, and it took government intervention to change that on a broad scale in our country.

| Name | Age |

|---|---|

| Sophia Nelson | 1 year |

| Mary Fending | 7 months |

| Agnes Foundling | 3 months |

| Edwin Alexander | 8 months |

| Heidel Wenzel | 4 months |

| R. Patem | 21 days |

| Aug. Begmane | 6 months |

| Henry Lunke | 6 months |

| John Buckley | 6 months |

| Edw. B. Wood | 6 months |

| Carl Peterson | 6 months |

| Baby Schmidt | 4 months |

| Baby Parsons | 3 months |

| Baby Moleta | 7 months |

| Charles Hoffman | 4 months |

| Joseph Bechinger | 2 months |

| Martin Cheska | 9 months |

| William J. Cullen | 1 year, 3 months |

| John H. Nip | 1 month, 2 days |

| Henry Erickson | 6 months |

| Thomas Erickson | 5 months |

| Victor Astel | unrecorded |

| Thomas Cabona | 2 months |

| O.M. Fenbert | 2 months |

| Chr. Keller | 11 months |

| Katherine Webar | 4 months |

| Ernst Amos | 3 months |

| C. Or P. Isacson | 3 months |

| Edwin Oleson | 1 year, 3 months |

| H.L. Zuick (or Quick) | 2 months |

| John F. Deuch | 8 months |

| Souri Keffer | 5 months |

| A. Fullen | 21 days |

| Milda Beetson | 9 months |

| Hedwig Noble | 9 months |

| William Henry | 5 months |

| Mary Kelsgerd | 9 months |

| Emma Stock | 1 year, 3 months |

| Mary Johnson | 6 months |

| Arthur Wilson | unrecorded |

| August Ferdinand | 9 months |

| Theresa Burgamester | 5 months |

| Louisa Schmidt | 5 months |

| H.W. Johnson | 3 months |

| Janie Augier | 4 months |

| Luce Lemy | 3 months |

| Albert Scheuer | 10 months |

| Baby Henner | 2 months |

| Illegible Baley | unrecorded |

References

If there is a Minnesota connection to be found, I must bring it up. I cannot help myself. ↩︎

Thompson, Mary E. and Arlene A. Keeling. "Nurses' Role in the Prevention of Infant Mortality in 1884-1925: Health Disparities Then and Now." Journal of Pediatric Nursing, vol. 27, no. 5, October 2012, pp. 471-478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2011.05.011 ↩︎

Thompson & Keeling note that "The precise cause of summer diarrhea is still unknown today; however, it was most likely a gastrointestinal infection from a strain of Escherichia coli, Salmonella, or Shigella bacteria or possibly rotavirus (Meckel, 1990)." Brosco states "Although many public health officials used epidemiologic studies to unearth the causes of infant diarrhea, other researchers turned to the new bacteriology to try to understand the abnormalities of the infant's gastrointestinal system. Both avenues of research produced many facts and theories but no simple answers." ↩︎

Thompson & Keeling. ↩︎

Thompson & Keeling. ↩︎

Thompson & Keeling. ↩︎

Thompson & Keeling. ↩︎

Holt, L. Emmett. The Diseases of Infancy and Childhood. New York, D. Appleton and Company, 1897. Pages 317-318. ↩︎

Holt. Pages 324-325. ↩︎

Meigs, G.L. "Other Factors in Infant Mortality than the Milk Supply and Their Control." American Journal of Public Health, vol. 6, no. 8, August 1916, pp. 847-853. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1286922/ ↩︎

Brosco, Jeffrey P. "The Early History of the Infant Mortality Rate in America: 'A Reflection Upon the Past and a Prophecy of the Future,'" Pediatrics, 1 February 1999, vol. 103, no. 2, pp. 478–485. http://doi.org/10.1542/peds.103.2.478 ↩︎

"Ramsey, Minnesota, United States records," images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-G5QL-914Q?view=explore : Oct 30, 2025), image 19 of 135; Minnesota. County Court (Ramsey County). Image Group Number: 004859978. ↩︎