Diphtheria 101 and the Dunn Family

Until I started researching family histories, I couldn't name any symptoms of diphtheria thanks to the routine vaccinations that made the disease irrelevant in my life. It was just another illness with a weird name that made me think of Little House on the Prairie. Books from the early 1900s or late 1800s sometimes described the suffering of infectious diseases—think of Beth March's death by scarlet fever in Little Women—but the authors were writing in time periods where they could assume many or all readers knew these illnesses and how terrible they were.

Since we live in the future, this is a quick Diphtheria 101:

It is appropriate to describe diphtheria as torturous. It instilled fear in communities when it appeared in town—people knew the terrible toll the disease could take on them and their families. Diphtheria is highly contagious and, left completely untreated, has a 50% fatality rate. Its unique (and uniquely unsettling) feature is the way it affects the throat, nose, and airway because it is more than just a sore throat. It creates a thick gray or black coating, or membrane, that can lead to severe difficulty with breathing. The disease can lead to asphyxiation (suffocation) because of the membrane, but it can also spread to the bloodstream and damage organs like the heart and kidneys or lead to paralysis.

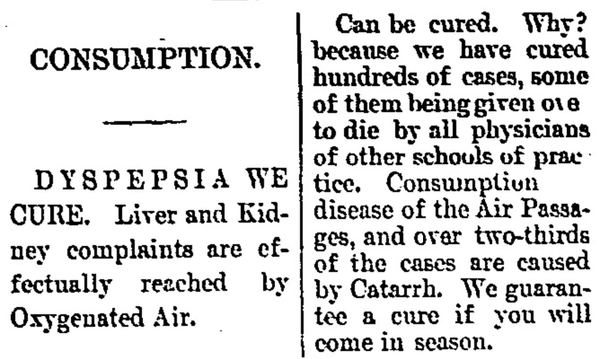

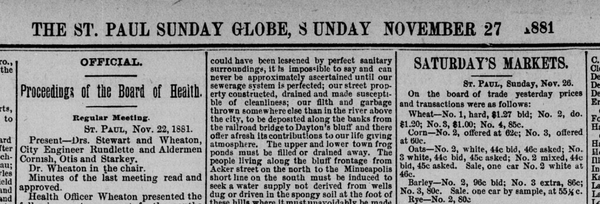

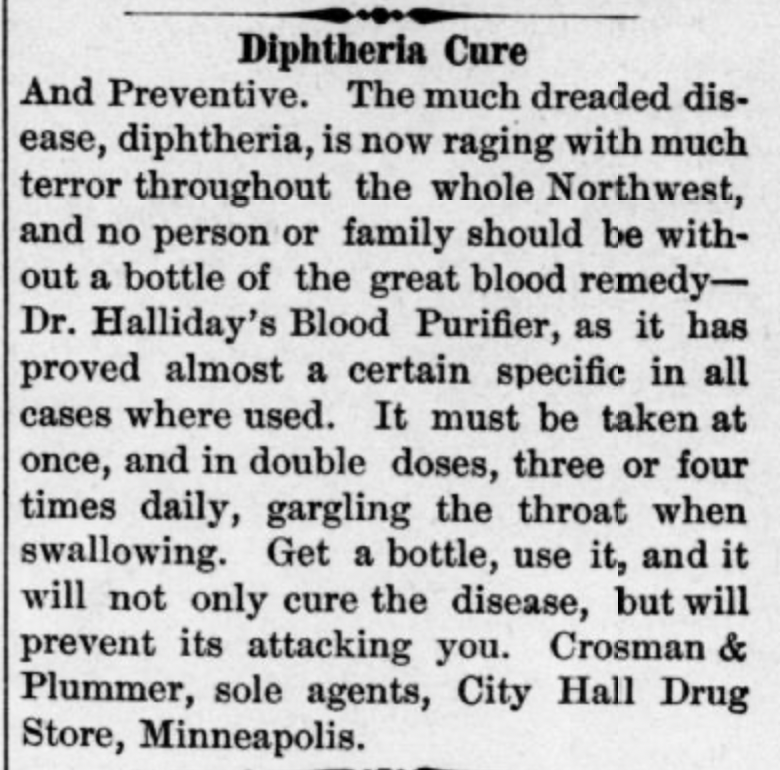

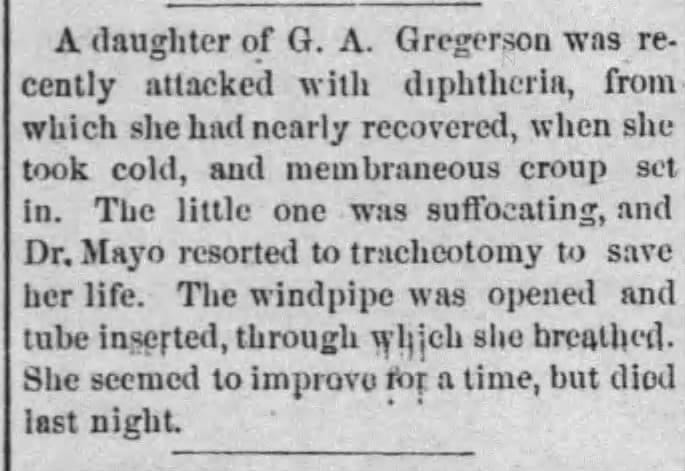

It's the kind of disease that makes people desperate for any prevention or solution, which they simply didn't have. Quack remedies for all kinds of illnesses were advertised in the papers of the time, as the featured image in this post highlights, but people were desperate for hope and physicians at the time lacked prevention and treatment options—those would only come years later with scientific progress. In this November 1881 news story, Dr. Mayo (likely William W. Mayo, father of the Mayo Clinic founders) attempted a tracheotomy on one young patient who was suffocating due to the membrane that was blocking her airway. It provides an illustration of just how life-threatening that membrane could be.

Torture really is the right description for this illness. The death registers provide us with a list of the most basic facts of a death and some potential questions to ask, but it is one thing to know that these people died of a disease and quite another to be able to imagine what the experience of their deaths were like. I will stick to the facts, but the way diphtheria kills is not mysterious and these people suffered through what we know its symptoms were (and are).

Katie, Bridget, and Stephen Dunn

I have an affinity for the Irish immigrant families of St. Paul—I come from several of them myself. We are notoriously difficult to track in records because of commonly shared first and last names. Without a unique trade or place of work in censuses or old city directories, you have to rely on consistency of family units (names, ages, places of birth) and residences.

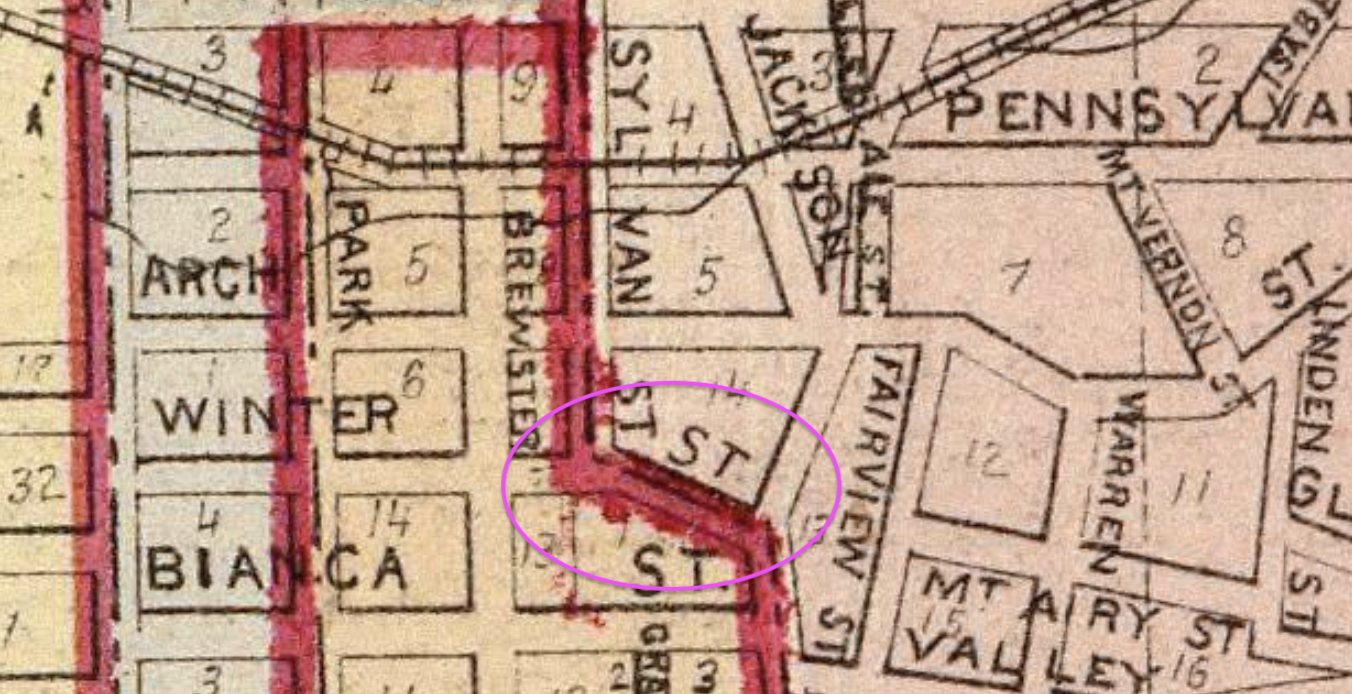

What we know about John and Sabina[1] Dunn is that they were Irish immigrants who lived at Winter & Jackson Streets[2] in St. Paul between 1875-1881. The couple had three living children: Stephen, Bridget, and Katie[3]. Many of their neighbors came from the same background as the Dunns: Irish immigrants with American-born children.

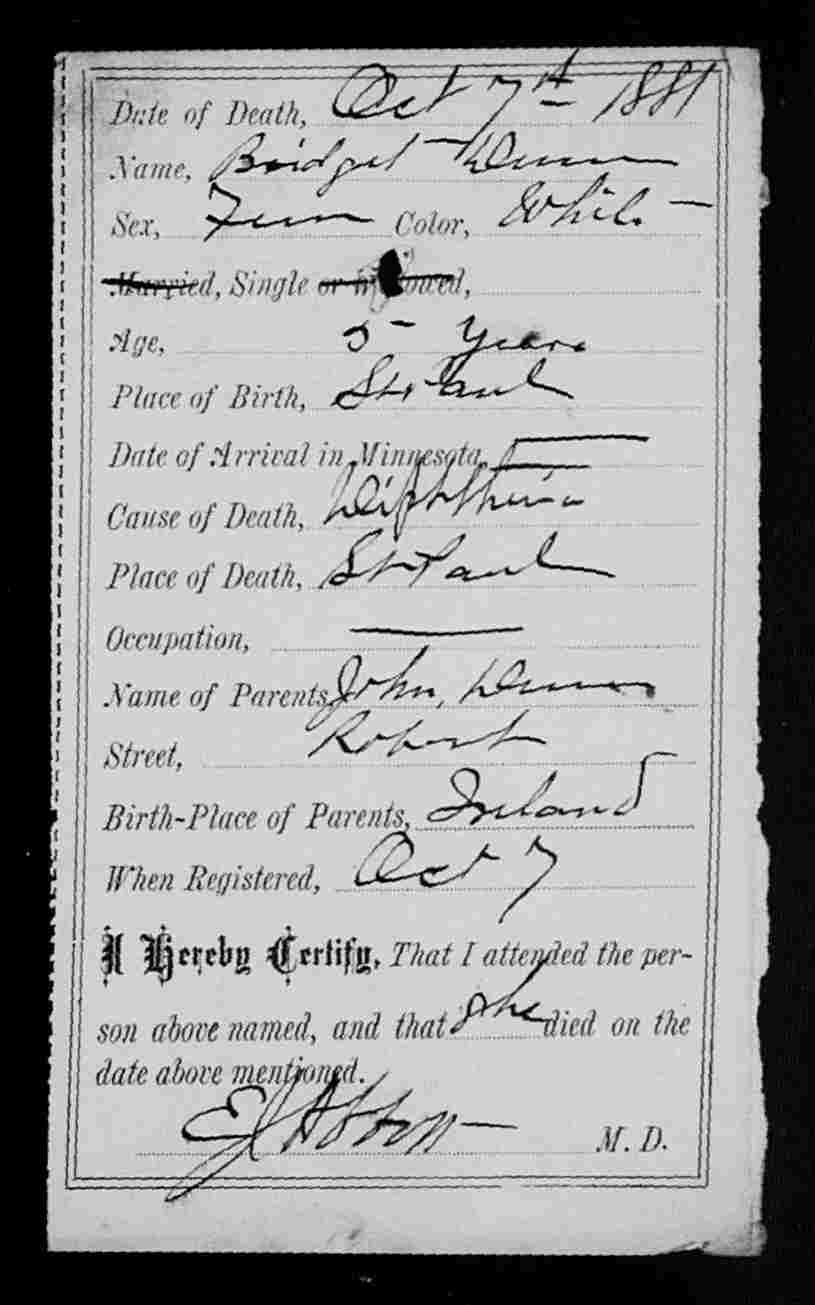

The three Dunn children were infected with diphtheria in the fall of 1881. Katie, the three-year-old, died first on September 23. Stephen, the seven-year-old, died a few days later on September 28. Bridget—their last living child—died a little over a week later, on October 7. She was five.[4] Bridget's death certificate (below) is an example of the original sources the death registers were created from. The physician who attended to her (Dr. E.J. Abbott) certified her death.

There are no obituaries or death notices for the children, which wasn't unusual at the time. John Dunn and the family's tragedy is mentioned briefly in the "Local Laconics" section of The Evening Journal the day after Bridget's death:

A little child of John Dunn, who lives on Robert street, was buried yesterday afternoon. Three children in this family have died within a short time with diphtheria and fever.[5]

The three children were buried at Calvary Cemetery, the 100 acre Catholic cemetery in St. Paul. There is a large, seemingly empty section on the left shortly after you go through its only entrance: the land all around it slopes down into a kind of valley with just one large tree in the middle of the grass. Though it looks empty, it isn't, it's just old. Stone markers sink over time, and old markers carved in wood don't survive intact for 144 years. The children are buried in Section 16, Block 25, Lots 68-70.[6]

As for John and Sabina—after 1881 it is unclear what happened to them. They had a son, David, about two months after Bridget died, but that is the last evidence I have of them living in St. Paul. I have found no evidence of any of their deaths, and no trace of David after his birth.[7]

The Dunn's tragedy speaks to me in part because I can't find them. Losing your children, all of your children, is a horror. I don't know how they handled it or whether they were able to rebuild their lives. I do know that they've been forgotten and forgotten people are difficult to find.

References

Sabina's name was spelled differently in different documents—sometimes as Sophina, sometimes Sophia. I chose Sabina as it seems that people were more likely to mistake "Sabina" for a more common name like Sophia than the other way around. The consistency of the children's names and ages, residence location, and lack of any other Sophia or Sabina Dunn who could be her allows us to have confidence that she is one person. ↩︎

Three sources support the residence location and time frame in which they lived there. The 1875 Minnesota Census, 1880 U.S. Federal Census, and St. Paul city directories for the years of 1875-1881. ↩︎

The source for most of the children's births is the "Minnesota, Births and Christenings, 1840-1980" database at FamilySearch. It is a finicky one where the indexed record doesn't link directly to the record. Stephen was a twin, but his sister Mary does not appear in the 1875 census or in any record I searched, so it is likely she passed away very early on or was stillborn. Bridget, "Briget" in the birth record,'s birth was recorded in 1877. Katie's year of birth is based on the 1880 census, the death register, and the Bakeman book on Calvary Cemetery. There appears to be a gap for available digitized 1878 records, which would explain the lack of a birth record for her. ↩︎

All sibling deaths can be viewed in different parts of the "Minnesota, County Deaths, 1850-2001" database with images at FamilySearch. Direct links are available for: Bridget's death, Katie's death, and Stephen's death. ↩︎

“John Dunn's children's deaths,” The Evening Journal, Minneapolis and Saint Paul, Minnesota, 8 October 1881, page 4, column 5. ↩︎

Bakeman, Mary Hawker, and Stina B. Green. 1995. Calvary Cemetery, St. Paul, Minnesota. Roseville, MN: Park Genealogical Books. ↩︎

If the family left Minnesota, the largely destroyed 1890 US Census creates a lengthy gap for the kinds of records that are used to trace people over time—19 years until the next federal census. That is enough time for deaths or household changes to make it very difficult or impossible to be certain you've found the correct people. Minnesota took a census in 1885, but I could not locate the family in that. ↩︎