The Many Tragedies of the Dittmans

When you are sick, you want a reason—you want a cure. If my child has a sore throat, I try to angle my phone’s flashlight so that I can see—how red is it? are there white spots? how many days has it been?—I have a sense of whether what is wrong requires a doctor’s visit and antibiotics for strep or if tea with honey and a day of video games is the best treatment.

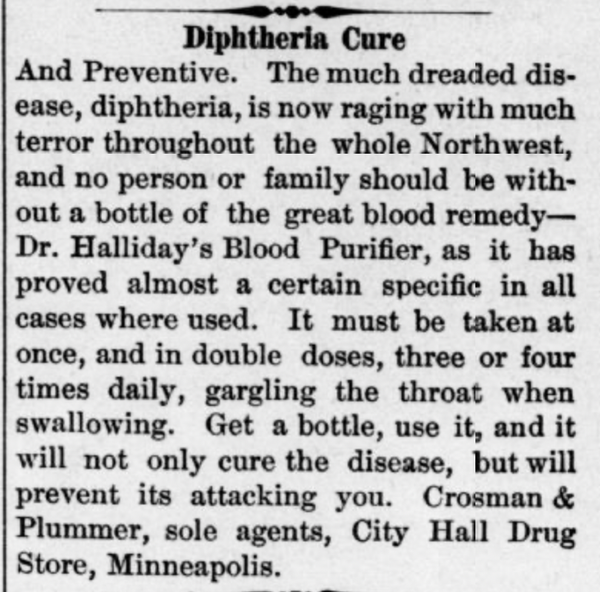

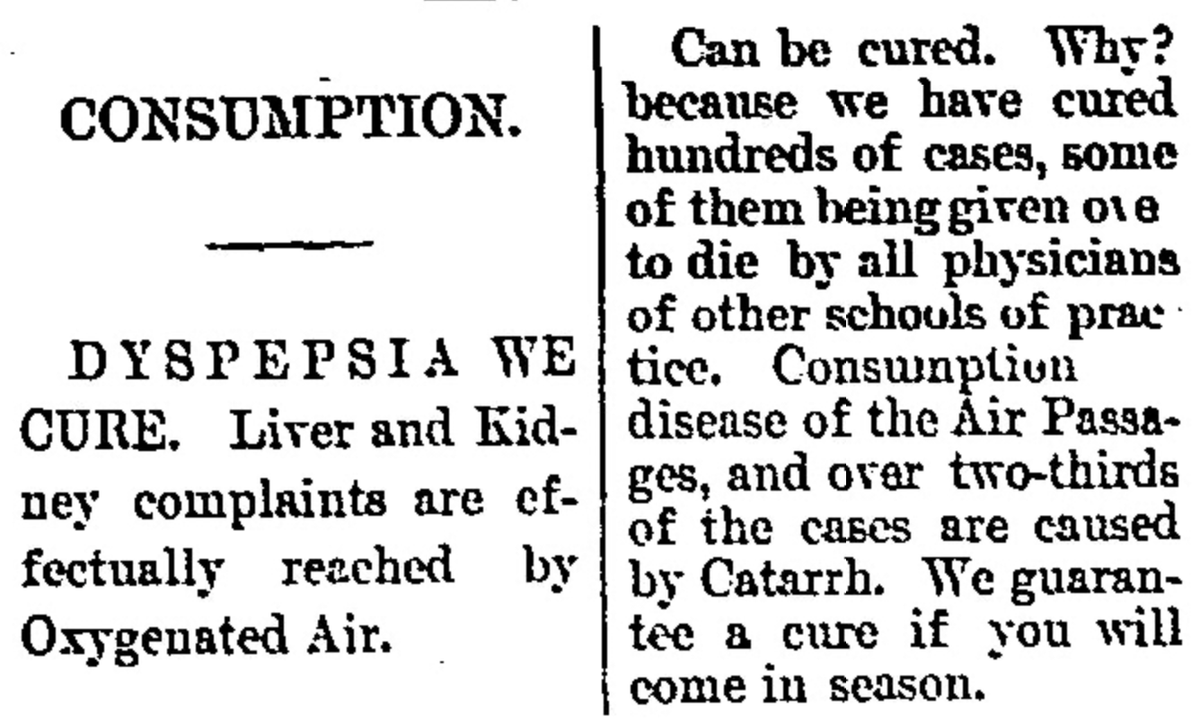

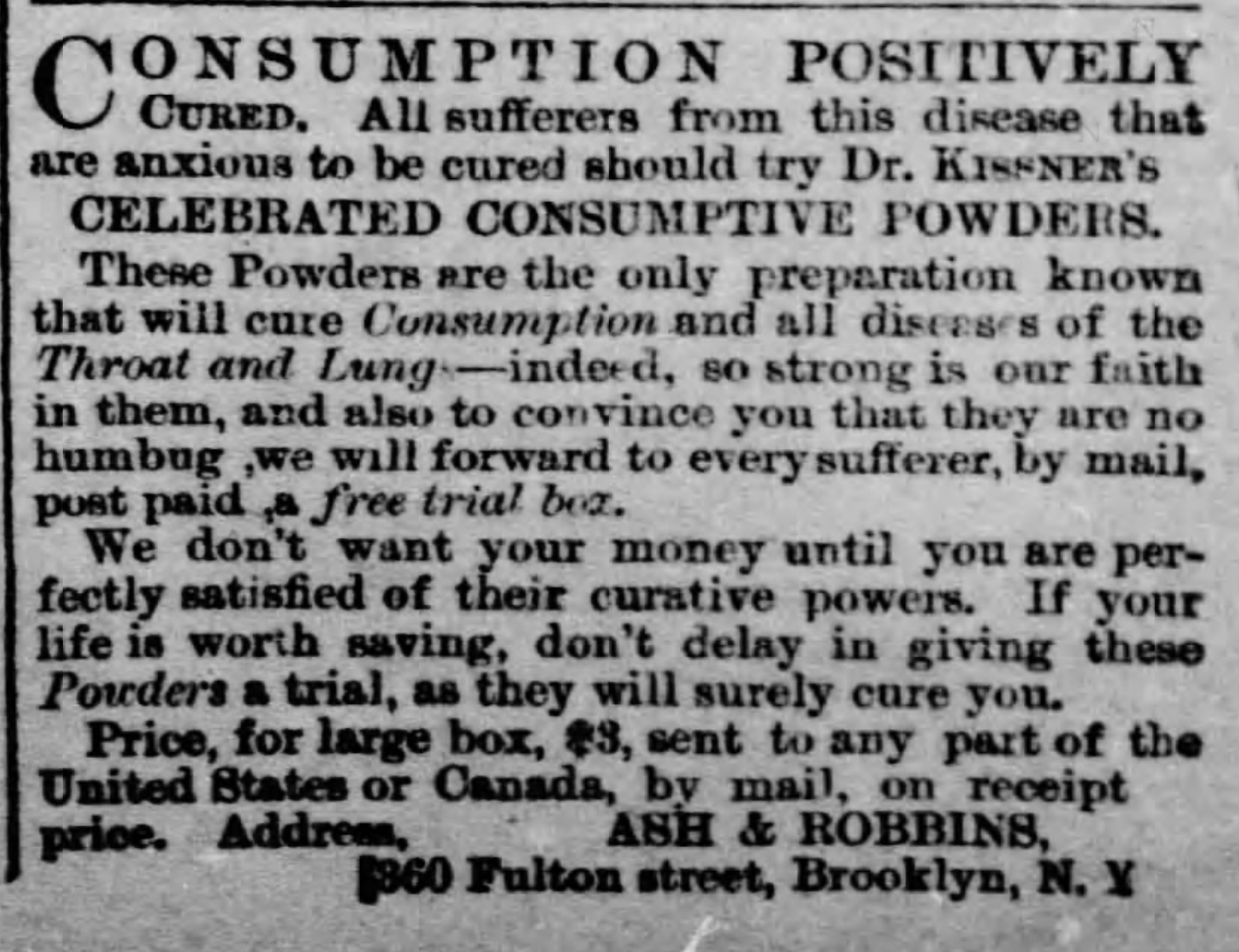

People wanted cures in the 1800s too, but they didn’t have them. They also had no regulations on food or drugs; those would not come until the 1900s and legislation passed by Congress, including the 1906 Food and Drugs Act, which “prohibited the interstate transport of unlawful food and drugs under penalty of seizure of the questionable products and/or prosecution of the responsible parties.”[1] I do not know what was in Dr. Townsend’s Oxygenated Air, which you could order from Providence, Rhode Island, but in addition to claiming to cure consumption the product also supposedly cured bronchitis, asthma, blood diseases, and cancers and tumors.

"Dr. Townsend’s Oxygenated Air will purify the blood in one-third the time that any other known remedy can. Why? because to inhale Oxygenated Air it goes direct to the Lungs and passes through the tissues and comes in direct contact with the blood as it is forced into the Lungs by the action of the heart. All the blood in our veins returns to the heart every four minutes if the blood is good, and forced from the heart to the lungs, and the more oxygen you inhale into the lungs the more you purify the blood. When Oxygen comes in contact with the impurities in the blood it carbonizes and burns, causing the blood to be heated so that it warms every part of the body, as it goes on its revolutions through the system. If your blood is pure, you cannot be sick. We drive Mercury and all other impurities out of the blood. We guarantee to purify the blood in one-third the time of any other known remedy.”[2]

The family in this vignette suffered far too many tragedies, but they were not alone in that experience. When you start really pulling the threads—how old the different siblings were when they died, what they actually died of, etc.—what you often find are conditions we cannot relate to and that we would find unacceptable.[3]

The Dittmann/Dittman Family

Names of immigrants from places like Germany often changed after some time in America. Wilhelm became William, a last name like Dittmann sometimes dropped the last “n” out of convenience. I use the Americanized last name and first names after this section for consistency.

Because the family is medium-sized with two different mothers, I've provided a brief summary of the family structure with the children's births noted.

- Wilhelm (William) Dittmann and Johanna Rehwald

- Emilie b. 1865, Berlin, Prussia (arrived in US 1869)

- Wilhelm (William) Dittmann and Elvire (Elvira) Szemioneck (arrived in US 1869)

- Wilhelm (William) b. 1868, Berlin, Prussia (arrived in US 1869)

- Samuel b. 1870, Dayton, OH

- Frank b. 1872, St. Paul, MN

- Martha b. 1874, St. Paul, MN

- Maria (Mary) b. 1877, St. Paul, MN

None of the Dittmans died of old age. I started to research them because, like the Dunns, they lost three children to diphtheria in 1881. Unlike the Dunns, I was able to trace their lives from Europe onward, and can provide a fuller picture of what what happened to the parents and siblings.

Genealogical Research Note

When you trace a family over time, you will find inconsistencies: a census taker who mangled a foreign first or last name, a record that was either scanned or transcribed incorrectly, and possible name mimics. You learn how to work through and past these issues, methodically considering alternatives or identifying reasons for conflicting data, and knowing what kinds of resources are available for different times and dates. I will write more about that in a separate, later post.

Berlin, Prussia, 1865-1869

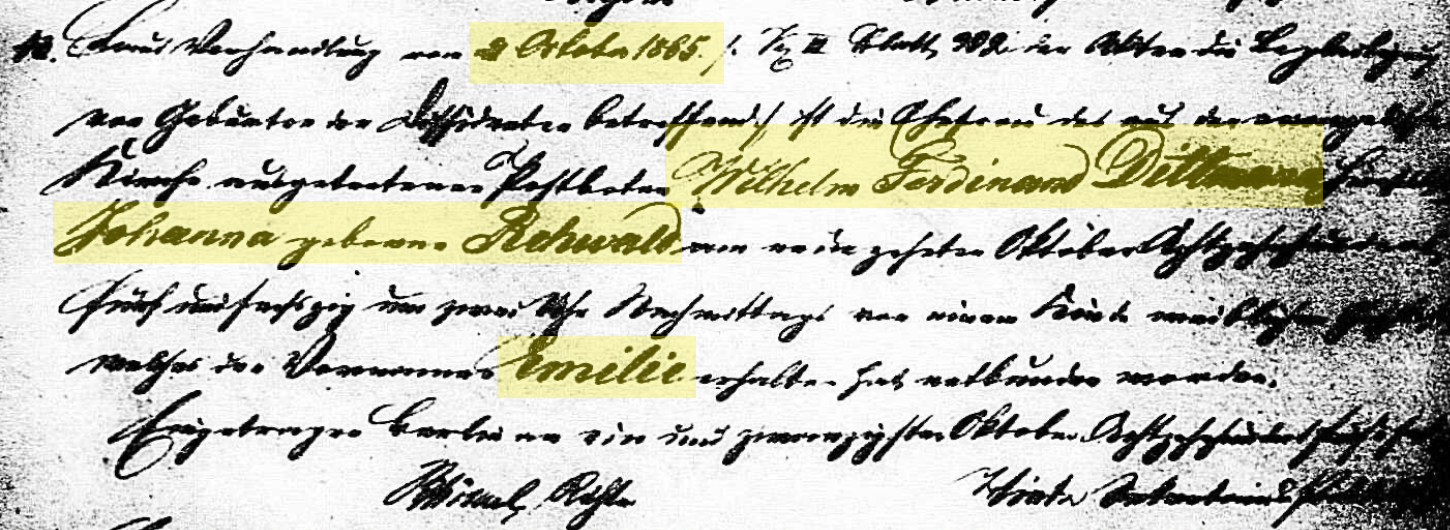

Emilie was the oldest of the Dittman children, born in 1865 in Berlin[4] to William Dittman and Johanna Rehwald. Johanna died at the age of 33 the following year of Unterleibsentzündung according to her German record—peritonitis.[5] There is no way to know if the abdominal infection resulted from a burst appendix, pregnancy or childbirth complications, or any other cause that simply couldn’t be adequately treated in those days.

Marrying relatively quickly after the death of a spouse when you had a young child was not unusual, and that is what William did. He married Elvira Szemioneck 8 months after Johanna’s death[6] and William, Jr. was born in 1868 in Berlin.[7]

Sometimes people living now draw the conclusion that, because life was so full of hardship and death, our ancestors didn’t feel as strongly about their families and were somehow immune to early deaths as a fact of life. This simply isn’t broadly true, and there are often little signs of the way the memory of deceased family was carried on. In Emilie’s case, it is that Johanna was named on her death certificate as her mother. Emilie was only a year old when her mother died; a name that lives on is a sign that she was talked about years after her death and that the memory of her presence remained.

Coming to America and Minnesota: 1869-1873

William, Elvira, Emilie, and baby William departed Hamburg on June 18, 1869.[8] They changed ships in England, arriving in the US on the Nebraska[9] 18 days later on July 6.[10] In the Hamburg ship manifest, William’s occupation was listed as schneider, or tailor. His work as a tailor made the family easily identifiable as they made their way from New York City to Minnesota. They lived in Dayton, Ohio, for a short period of time. Their first American-born son, Samuel was born there in 1870.

Saint Paul: 1873-1896

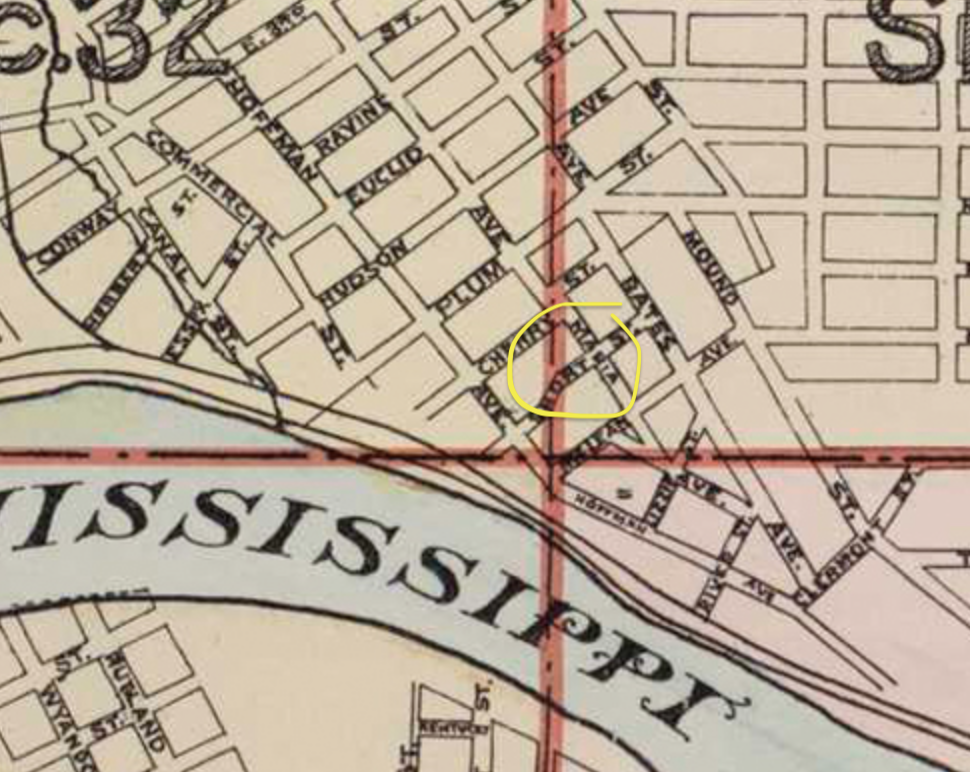

William and Elvira had three more children in St. Paul: Frank (1872), Martha (1874), and Maria (1877).[11] The family lived in the same location[12] for the entirety of their recorded time in St. Paul and the house Elvira built in 1882 is still standing, but the look of the area has changed. I-94 is now a block north of the house and Wicaḣapi[13] is just a couple blocks east.

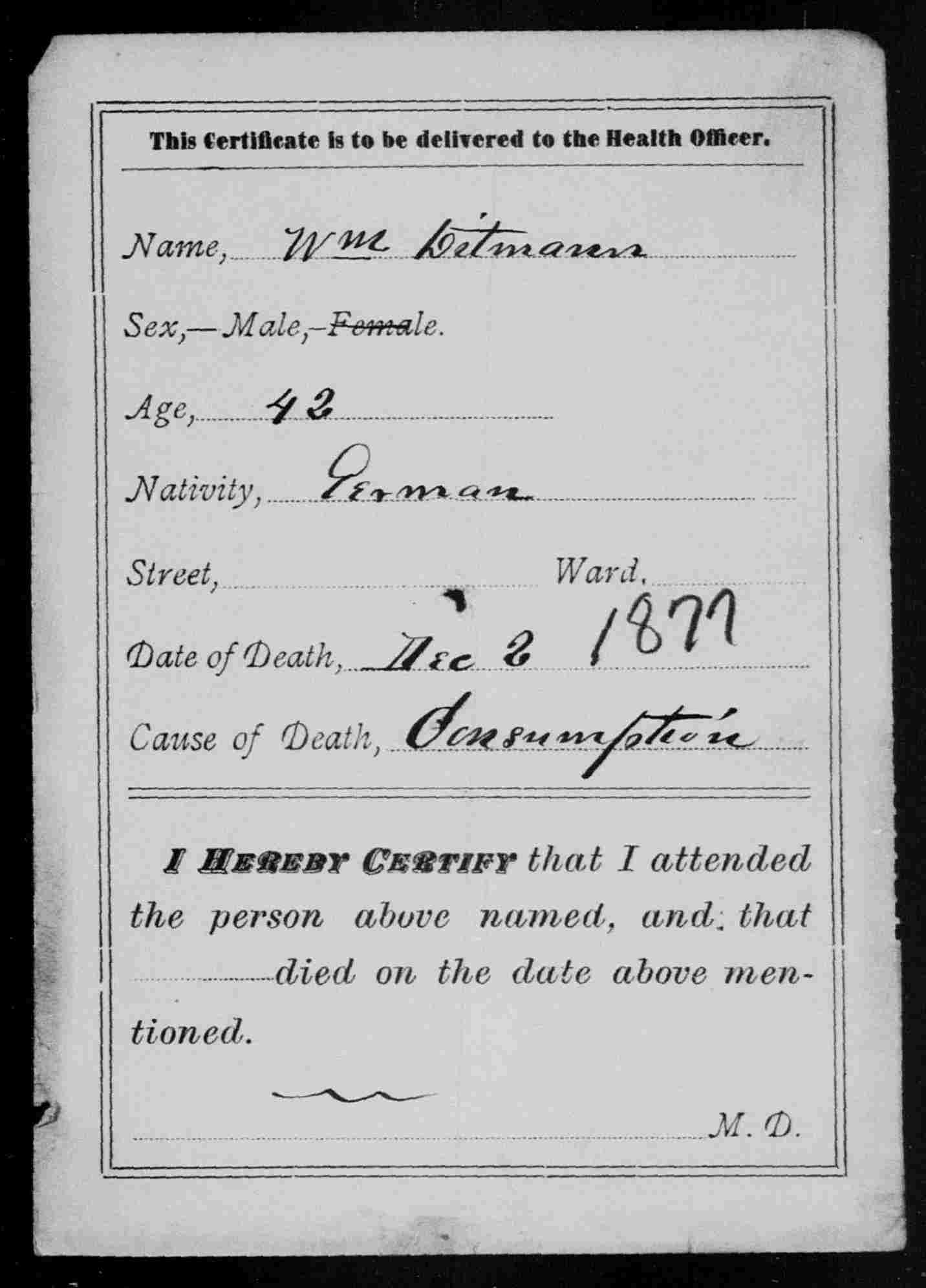

1877: Consumption

William, Sr. was only 48 when he died of "consumption" (tuberculosis) in December 1877.[14] There were no effective treatments at the time, nor a broad understanding of the cause of the illness. This was before the discovery of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria, and when it was often thought to be somehow hereditary or constitutional. We humans are notorious for finding patterns in anything, and enough people had TB that you could come up with a story: artistic temperament, heritability, etc.[15]

Medical texts that detailed diseases and treatments show how limited their toolbox was even into the 1890s, years after William's death. In Sir William Osler’s 1892 medical text, treatment options included tuberculin (which did not work), ensuring patients ate enough to prevent wasting away, and fresh air or vacation to stimulate the appetite. Recommended medicines were not intended to cure patients, but instead focused on on keeping patient nutrition up.[16] The doctor wrote:

“The indications for alcohol in tuberculosis are enfeebled digestion with fever, a weak heart, and rapid pulse…In the advanced stages, particularly when the temperature is low before eight and ten in the morning, whisky and milk, or whisky, egg, and milk may be given with great advantage. The red wines are also beneficial in moderate quantities.”[17]

As I said before: it doesn’t matter what time we live in, we want cures and treatments for our suffering—but knowledge changes over time. This is something that is a dangerous component of the “wellness” and anti-vaccine activism movements, in which medicines of the past are idealized. The past would trade with us. Antibiotics over whiskey and milk. Prevention over suffering in the first place.

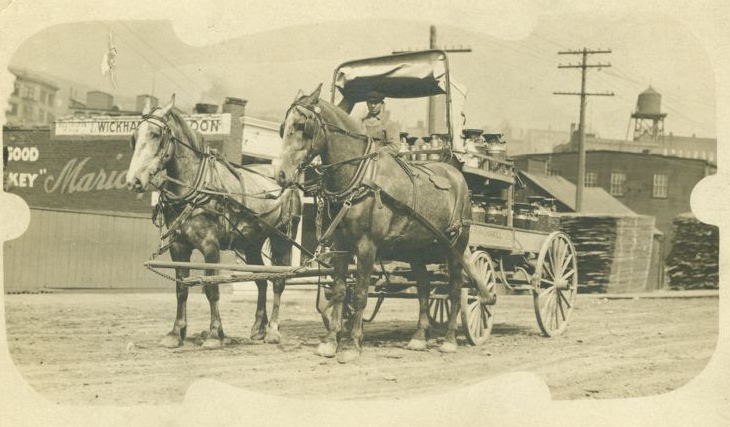

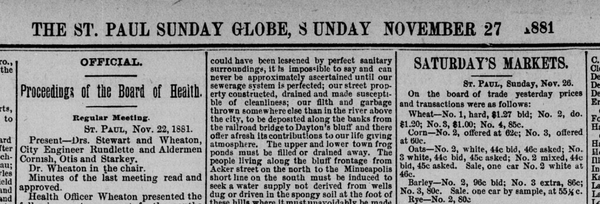

Curative (and completely unregulated) advertising were in most newspapers. Some have images, some look like news stories—if they had had social media, it would have been full of them as well.[18]

When William died, his youngest child was seven months old. Elvira never remarried, and was raising the five children alone. By the 1880 census, if it is accurate, the only children who went to school were Frank (8) and Martha (6). William’s (12) occupation was listed as “errand boy” and while neither Emilie (14) nor Samuel (9) had an occupation listed, they also weren’t marked as attending school.

1881: Diphtheria

Four years after William's death, Elvira lost three children to diphtheria. Mary (4) died October 4, Martha (7) died October 10, and William (13), died October 16.[19] My piece on the Dunn family goes into more detail about diphtheria in general, but a 2024 comment in the Correspondence section of The Lancet described the experience of these deaths with brutal succinctness: “The cruelty of lethal diphtheria is difficult to exaggerate. A child who is slowly strangled by an unstable expanding coagulum of necrotic tissue in the upper airway, a toxic and untreatable rapidly progressive cardiomyopathy or, after surviving these, death from neuropathic acute respiratory failure.”[20] It is difficult to overstate how significant the impact of widespread vaccination is on these devastating illnesses.

1896: Bronchopneumonia and Typhoid

By 1896, Elvira was the only family member remaining in St. Paul. A family (the Murnaghans) lived with her at 661 Short Street; probate records[21] indicate that her son, Frank, was the owner of the property, so the Murnaghans may have been lodgers who provided her income.

Samuel left St. Paul in the late 1880s, and Frank around the time he turned 18. They both lived in Chicago in 1896.[22] Emilie married her husband John in Washington, D.C. in 1890 and they lived in New York City.[23]

Frank and Elvira died within a month of each other in 1896. Elvira died of typhoid in May at the age of 64,[24] which is spread by contaminated food or water, or through lack of handwashing by an infected person that, if not treated by antibiotics, can be fatal. Osler’s 1892 text described the deaths doctors saw people experience at the time: the high fever and dehydration from diarrhea can be deadly, but in people who remained sick it could lead to heart failure or hemorrhage.[25]

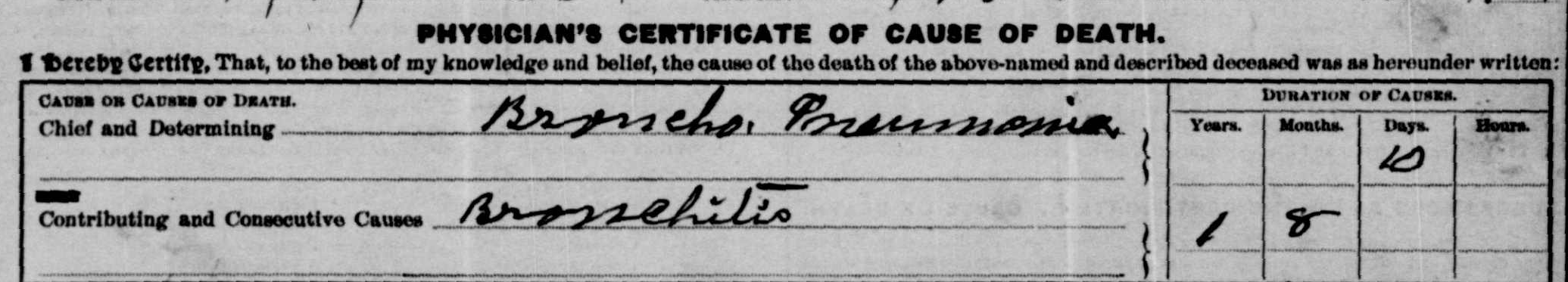

Frank died a month earlier of bronchopneumonia in Chicago at the age of 24.[26] His death is the first to have a more complete explanation. This kind of information is useful because it provides information on whether a death was sudden or a result of another medical issue.

Frank had been suffering since he was about 22 years old with what the doctor called bronchitis before his death of bronchopneumonia. Though his death certificate had more information than earlier ones, there was no explanation for why he had been sick for so long.

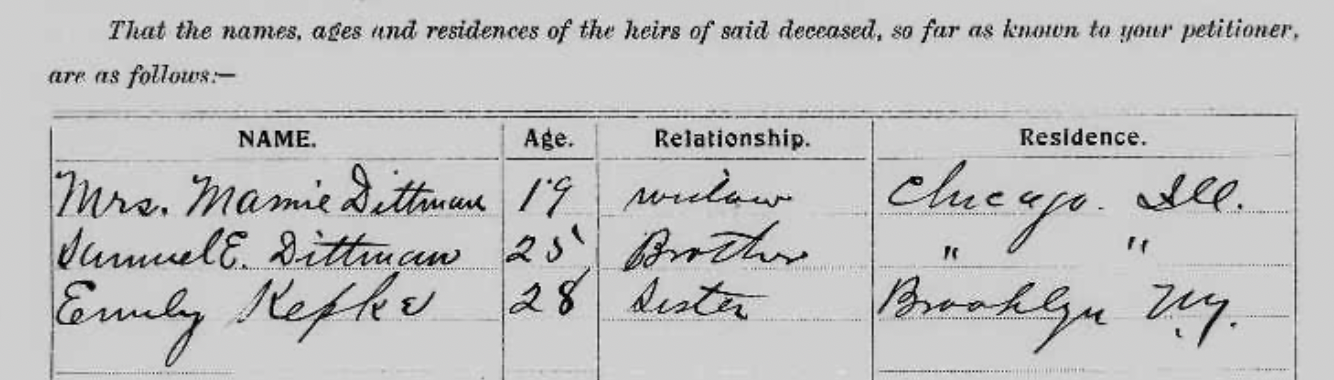

Samuel was either in St. Paul with his mother when she died, or got there shortly after, because he filed probate paperwork on May 13, 1896, about a week after her death.[27] For the purposes of this story, probate records give us a few pieces of information about their lives: Frank had recently married, leaving a 19-year-old widow (Mamie); Emilie lived in Brooklyn; and Samuel lived in Chicago.[28]

By the mid-1890s, probate was reasonably well-organized in St. Paul. They typically listed people related to the deceased (their heirs) along with ages and locations, so if there was a family member that was previously unknown or one that you lost the trail on in records, this is a way you could out where family members were.

1912: Heart Failure

It was Emilie’s death certificate that really made me wonder about whether the siblings who lived had been affected long-term by the family’s diphtheria tragedy, though there were so many possible paths to chronic illness (including childbirth) that it's something that will remain unknown. Emilie was 46 when she died at home of “valvular disease of [the] heart,”[29] which she had endured since she was 26 years old. She suffered from heart failure for three months before dying.

All of the deaths make me angry—not about the past, but about the present and how vulnerable our perception of the past is to people who want to make money off an image of a perfect, healthy, better life that only existed before modern medicine and public health. It was not better. Emilie’s life is such an example—she married a physician and seems to have had access to anything money could buy. However, it couldn’t buy a life free of illness. Not for her, but also not for her younger son. He was diabetic—and he died when he was nine; his death record notes that he died of diabetes and was in a coma.[30]

1925: Samuel

Samuel was 54 years old when he died;[31] he had lived in New York City for 20 years before returning to Chicago[32] in 1922. His death was officially ruled carbon monoxide poisoning,[33] but a Brooklyn Daily Eagle article about his death strongly implies that he died by suicide[34] by mentioning a “nervous breakdown” four months prior to his death.

I don’t want Samuel’s death to serve as a kind of ultimate tragic culmination of the family. Struggles with mental health are not a modern problem, and like every other health challenge the family faced—there were not adequate tools to help him. At 54, he was older than his father had been when he died; and he outlived all his siblings (in most cases by decades).

So much of what this family suffered would have been prevented or treated now: water sanitation to prevent typhoid, vaccines to prevent diphtheria, antibiotics to treat tuberculosis, medication and therapy to support people who are struggling with mental health, and so on. We don't have to imagine the past—the records are right there, showing us what things were really like.

Summary Table

This is a table of the family, age at death, and cause arranged in order by date of death.

| Family Member | Age at Death | Cause |

|---|---|---|

| Johanna Rehwald 1833-1866 (mother of Emilie) |

33 years | Peritonitis |

| Wilhelm (William) Dittman 1839-1877 (father) |

48 years | Consumption (Tuberculosis) |

| Mary Dittman 1877-1881 |

4 years | Diphtheria |

| Martha Dittman 1874-1881 |

7 years | Diphtheria |

| Wilhelm (William) Dittman 1868-1881 |

13 years | Diphtheria |

| Frank J. Dittman 1872-1896 |

24 years | Bronchopneumonia |

| Elvire (Elvira) Szemioneck 1831-1896 (mother of all other children) |

64 years | Typhoid |

| Emilie Dittman 1865-1912 |

46 years | Heart disease |

| Samuel Dittman 1870-1925 |

54 years | Carbon monoxide poisoning |

A final note

Contrary to what I write about in this project, I don’t spend most of my time focused on deaths—I notice them, just like I notice occupations, newspaper coverage, and other components of peoples' lives. The massive scientific misinformation campaign we currently face is dangerous in ways many people don’t fully appreciate, and there is a need to paint a real picture of the past.

However, I couldn’t help but have my attention drawn to one other item about this family. A family genealogist uploaded a letter sent by Emilie’s son, John, to Reverend Ralph D. Abernathy with a donation in support of the Montgomery bus boycott in 1956. It says:

I read in yesterday’s paper that Mayor W.A. Gayle of your city revealed that he has received $56 in contributions from fifty-three citizens of Atlanta for the Montgomery bus lines.

I also read that the leaders of your boycott announced that they are to increase their car pool fleet and are opening permanent offices with a paid secretarial staff.

I am happy to send you herewith a check for $56 from one citizen (white) of Brooklyn, as a contribution toward the expenses of your car pool office.

I like that as a note to end on for the family. An actually fun fact; an otherwise unknown act among a sea of other Americans taking unknown actions to create change in our country during incredibly difficult times.

References

“Part I: The 1906 Food and Drugs Act and Its Enforcement,” U.S. Food & Drug Administration, last updated 24 April 2019. ↩︎

“Advertisement: Dr. Townsend’s Oxygenated Air,” The Minneapolis Tribune, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 25 March 1877, page 2, column 7. ↩︎

I want to be very clear: I am speaking about our expectations within the US about our lives here and now. There is not equitable access to vaccines, treatments, and other disease interventions in countries, and this is a moral failing on the part of high income countries. My concern as I write these pieces is that in the U.S. there are too many people don’t realize how dramatically our health has improved because of prevention and treatment. That attitude endangers efforts in places that have not benefitted from what we take for granted. For instance, the WHO efforts regarding the TB crisis and response are affected by the chaotic funding cuts of our current administration, and that endangers efforts to eliminate TB worldwide and harms real people right now who require treatment. ↩︎

“Berlin, Brandenburg, Prussia, Germany records,” database with images, FamilySearch, entry for Emilie Dittmann, born October 1865, Berlin, Brandenburg, Prussia, image 934 of 1959, image group number 102526781. ↩︎

“Germany, Lutheran Baptisms, Marriages, and Burials, 1500-1971,” database with images, Ancestry.com, entry for Johanna Rehwald, died 22 November 1866, Berlin, Brandenburg, Prussia: citing “Kirchenbuch, 1694-1882,” Evangelische Kirche, Luisenstädtische Kirche Berlin, FamilySearch, microfilm number 70135, image 164. ↩︎

“Berlin, Brandenburg, Prussia, Germany records,” images, FamilySearch, entry for Wilhelm Dittmann and Elvire Schemioneck, married 24 July 1867, Berlin, Brandenburg, Prussia, image 1351 of 1959, image group number 102526781. ↩︎

“Berlin, Brandenburg, Prussia, Germany records,” images, FamilySearch, entry for Wilhelm Dittmann, born May 1868, Berlin, Brandenburg, Prussia, image 946 of 1959, image group number 102526781. ↩︎

“Hamburg Passenger Lists, 1850-1934,” database with images, Ancestry.com, entry for Wilhelm Dittmann, departure 18 June 1869, citing Staatsarchiv Hamburg; Hamburg, Deutschland; Hamburger Passagierlisten; Volume: 373-7 I, VIII B 1 Band 015; Page: 637; Microfilm No.: S_13121. ↩︎

The Nebraska was a ship used by the Guion Line. Wikipedia has images of other ships and a schematic of the layout if you’re interested in seeing what that was like. ↩︎

“New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957,” database with images, Ancestry.com, entry for Wilhelm Dittmann, arrival 6 Jul 1869. ↩︎

Mary's (born 28 May 1877, img 162 of 236) and Martha's (born 6 February 1874, img 10 of 236) births are located in: "Minnesota, County Birth Records, 1863-1983," images, FamilySearch, Ramsey > Births, 1874 - 1879, vol. B; county courthouses, Minnesota.

Frank’s birth record is not available online, so his age is drawn from:

Illinois, Cook County Deaths, 1871-1998", FamilySearch, entry for Frank J Dittman, died 27 Apr 1896. ↩︎The family is found at this location in the St. Paul City Directories in the years 1873-1896.

Census records show who lives at the residence between 1875-1895:

1875 Minnesota state census, Ward 5, Saint Paul, Ramsey, family 814, William Dittmann family, FamilySearch.

1880 U.S. census, Saint Paul, Ramsey County, Minnesota, population schedule, enumeration district (ED) 18, p. 343A stamped, dwelling 117, family 125, Elvira Dittman family, FamilySearch.

1885 Minnesota state census, Ward 5, Saint Paul, Ramsey, p. 18, family 137, Elvira Dittman family, FamilySearch.

1895 Minnesota state census, Ward 2, Saint Paul, Ramsey, p. 2, family 63, Elvira Dittman (with Michael Murnighan family), FamilySearch. ↩︎Wicaḣapi (pronounced we-CHA-ha-pee) was previously known as “Indian Mounds Regional Park.” ↩︎

"Saint Paul, Ramsey, Minnesota, United States records," images, FamilySearch, entry for William Dittman, died 2 Dec 1877, image 1776 of 2140, St. Paul, Minnesota, Department of Health. ↩︎

John Green’s recently released book “Everything Is Tuberculosis” is an engaging read about TB (current and past). ↩︎

Osler, Sir William, The principles and practice of medicine: Designed for the use of practitioners and students of medicine, New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1892, p. 252. ↩︎

“Ad for Dr. Kissner’s Celebrated Consumptive Powders,” The Minneapolis Tribune, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 31 Dec 1877, page 3, column 8. ↩︎

All records are from “Minnesota, Birth and Death Records, 1866-1916", FamilySearch.

Maria Dittmann (4 Oct 1881), Martha Dittmann (10 Oct 1881), William Dittmann (16 Oct 1881). Note: William’s death record says he’s 11, but he’s older. ↩︎The author was specifically addressing the appalling current conditions regarding access to medicine in less resourced or conflict-affected locations.

White, Nicholas J. 2024. “Death from Diphtheria.” The Lancet 403 (10444): 2590–91. ↩︎Ramsey County, Minnesota, probate case file 8390, “In the Matters of the Estate of Frank J. Dittman,” images 93-107. ↩︎

See St. Paul City Directories in the years 1873-1896 for Dittman/Dittmanns listed. ↩︎

Emilie’s residence is established through her marriage place and date, and the location and dates of her children’s births. Brooklyn, New York, “Kings (Brooklyn) Birth Certificates,” database with images, Historical Vital Records: The New York City Municipal Archives, 3833, Paul Kepke, 19 January 1897.

Brooklyn, New York, “Kings (Brooklyn) Birth Certificates,” database with images, Historical Vital Records: The New York City Municipal Archives, 36834, John Kepke, 17 October 1891.

“Washington, District of Columbia, U.S., Marriage Certificates, 1870-1920,” database with images, Ancestry.com, marriage index, Emilie Dittman and John Koepke, 23 April 1890, Washington, D.C., certificate no. 13857; citing District of Columbia Public Library; Washington, DC, USA; Washington, D.C. Marriage Certificates, 1870-1920. ↩︎"Minnesota, Birth and Death Records, 1866-1916", FamilySearch, Entry for Elvira Dittman, 08 May 1896. ↩︎

"Illinois, Cook County Deaths, 1871-1998", FamilySearch, Entry for Frank J Dittman, 27 Apr 1896. ↩︎

Ramsey County, Minnesota, probate case file 8390, “In the Matters of the Estate of Frank J. Dittman,” images 93-107.

Ramsey County, Minnesota, probate case file 8389, FamilySearch, “In the Matters of the Estate of Elvira J. Dittman,” images 73-92. ↩︎“In the Matters of the Estate of Frank J. Dittman,” image 94. ↩︎

Kings County, Brooklyn death certificate no. 10782, Emily Kepke, died 26 May 1912; Department of Records & Information Services, “NYC Historical Vital Records,” images. ↩︎

Kings County, Brooklyn death certificate no. 6541, Paul Kepke, died 29 March 1906; Department of Records & Information Services, “NYC Historical Vital Records,” images. ↩︎

"Chicago, Cook, Illinois, United States records," images, FamilySearch, image 797 of 2728, entry for Samuel Dittman, died 10 April 1925, Illinois Public Board of Health Archives. ↩︎

“Samuel E. Dittman Dies,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 11 April 1925, p. 2, col. 6. ↩︎

"Chicago, Cook, Illinois, United States records," images, FamilySearch, image 797 of 2728, entry for Samuel Dittman, died 10 April 1925, Illinois Public Board of Health Archives. ↩︎